How Oncolytic Viruses Could Be a New Frontier in Transforming Cancer Treatment

ONCOLife |

20 November 2024

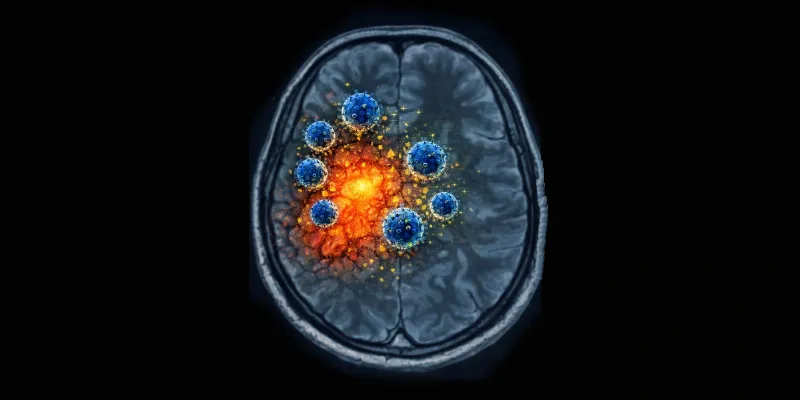

Oncolytic viruses are a very promising class of therapeutic agents, with a broad range of types. They not only infect and kill cancer cells, but also modulate the tumor micro-environment to enhance immune responses. In this exclusive interview with Dr. Thomas C. Heineman, Chief Medical Officer at Oncolytics Biotech, we explore the groundbreaking potential of oncolytic viruses.

Exclusive Interview with Dr. Thomas Heineman

Dr. Heineman analyzes the recent clinical efficacy results from the BRACELET-1 trial in HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer, which pave the way for a novel treatment option, currently expected to pursue FDA Accelerated Approval in a registration-enabling study. He shares insights into the unique mechanism of action of their novel oncolytic virus, pelareorep, which has shown promising results in the trial.

Click the picture to view the PDF version: Pg 26-29.

Oncolytic viruses not only destroy cancer cells but also modulate the tumor microenvironment to enhance anti-tumor immune responses. Could you provide some information about oncolytic viruses and their role in cancer treatment?

Dr. Heineman: Oncolytic viruses are a very promising class of therapeutic agents, with a broad range of types. These viruses naturally infect, replicate in, and kill cancer cells. What’s become clear over time, especially with pelareorep, the oncolytic virus we’re developing at Oncolytics Biotech, is that they primarily function by modulating the immune system more than by directly killing cancer cells.

Pelareorep is a naturally occurring isolate of reovirus, distinct in that it selectively infects cancer cells without affecting normal cells, and it is not genetically modified. This means it doesn’t require special handling. Unlike many oncolytic viruses, pelareorep can be administered intravenously, evading neutralization in the bloodstream, which allows it to target both primary tumors and metastases.

This makes it convenient for both patients and physicians, as it can be safely delivered in an oncology suite without requiring special procedures or intratumoral administration. This combination of selectivity, ease of administration, and immune system modulation makes pelareorep a particularly promising therapy in cancer treatment.

Could you elaborate on the mechanism of action of Pelareorep and how it stands out from other oncolytic viruses in terms of efficacy and safety, particularly in HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer?

Dr. Heineman: Pelareorep is a unique agent among oncolytic viruses because it’s a virus with a double-stranded RNA genome. When pelareorep infects cancer cells, it selectively releases its RNA into the cancer cells, triggering an inflammatory response.

This causes the upregulation of various chemokines, making the tumor more visible to the immune system. At the same time, pelareorep expands tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, which target the tumor directly. We believe pelareorep works by stimulating anti-tumor immune responses and modifying the tumor microenvironment, making the tumor more responsive to these immune responses.

In HR+, HER2- metastatic breast cancer, where immunotherapies have not historically been successful, pelareorep has shown particularly strong clinical data. Our studies clearly show an upregulation and expansion of T cells in the blood following pelareorep treatment, which suggests a powerful immune response.

This dual mechanism of action—modifying the tumor microenvironment and stimulating immune responses—makes pelareorep an efficient agent for targeting tumor cells.

BRACELET-1 study showed a median overall survival of at least 32 months in the Pelareorep+paclitaxel arm. What are the key factors contributing to this significant improvement?

Dr. Heineman: In the BRACELET-1 study, we compared pelareorep plus paclitaxel as the investigational arm to paclitaxel alone, which served as the control arm. In the control arm, the patients had a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 6.4 months, which is typical for this treatment. When pelareorep was added, the PFS nearly doubled to 12.1 months.

Regarding overall survival (OS), the control group had a median OS of 18.2 months, again typical for this population. However, in the pelareorep arm, median OS was not reached by the study’s end, with over half the patients still alive. Even with a conservative assumption that all patients would pass at their next clinical visit, the estimated median OS would exceed 32 months.

This strong PFS and OS benefit is likely due to pelareorep’s ability to make tumors visible to the immune system and stimulate T cell responses. The treatment enhances immune access to the tumor by modifying the tumor microenvironment through inflammatory effects, making it more accessible to immune attack.

BRACELET-1 included a cohort combining Pelareorep with avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 therapy. Could you share any preliminary observations on how pelareorep modulates the tumor microenvironment and potentially enhances the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors?

Dr. Heineman: In this study, we had an arm that included the checkpoint inhibitor avelumab, but it didn’t add any benefit to the treatment. This may be due to avelumab’s unique nature—it binds to the FC receptor, which paradoxically suppresses the early immune responses that pelareorep stimulates.

So, moving forward, avelumab is likely not the right combination partner. However, we don’t need it, as we are seeing strong effects without it. That said, other checkpoint inhibitors with different designs have shown real promise when combined with pela-reorep, particularly in gastrointestinal cancers like pancreatic cancer, where we’ve already seen impressive response rates.

Beyond breast cancer, Pelareorep has shown promise in pancreatic cancer. What is your vision for expanding its application to other tumor types, and are there specific cancer indications that you are focusing on for future studies?

Dr. Heineman: We have conducted several studies of pelareorep-based combination therapies in pancreatic cancer, and the results have been very promising. The most recent is the GOBLET study, where pelareorep was combined with standard chemotherapy (gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel) and the checkpoint inhibitor avelumab. In this study, we saw an impressive tumor response rate of over 60%, which is much higher than what you’d typically expect in this difficult patient population.

These findings, along with earlier studies, make us optimistic about pelareorep’s potential in pancreatic cancer, an area where developing new therapies has been challenging. We’re collaborating with GCAR (Global Coalition for Adaptive Research), an organization experienced in conducting well-designed studies.

We are actively working with them and their scientific experts to design our next study for pelareorep in pancreatic cancer, and we’re confident about moving forward based on our previous success. Additionally, in the GOBLET study, we’ve seen some promising data in a rare cancer population where patients have failed primary therapy. While the dataset is still small, the response rates are about three times higher than expected in this group, which has very limited treatment options.

We are expanding this arm of the study, and if the efficacy signal holds in a larger patient population, we’ll pursue further development of pelareorep combination therapy for this rare cancer with the goal of licensure.

As you look ahead, what are the key milestones and research goals for Oncolytics Biotech over the next five years? How do you envision pelareorep changing the standard of care for cancer patients?

Dr. Heineman: Over the next several years, we plan to develop pelareorep primarily for breast and pancreatic cancers. If data continues to look positive in anal carcinoma, we’ll likely explore that area as well. In the near future, we’ve identified a clear pathway for potential accelerated approval in breast cancer through a large Phase 2 study, which we hope to begin enrolling in the first half of next year, with results expected around 24 months later.

Similarly, we’re advancing our work in pancreatic cancer with GCAR on a similar timeline. We need to discuss both programs with the FDA, but previous discussions suggest we’re on the right path for both indications, and we feel confident about these development routes.

Comments

No Comments Yet!