Colibactin’s Molecular Blueprint Exposes How a Gut Microbial Toxin Triggers Colorectal Cancer

6 December 2025

Harvard scientists have defined the exact DNA cross-link created by colibactin, a gut microbial toxin associated with colorectal cancer. By revealing how a central α-ketoiminium group targets AT-rich sequences and generates the same mutational patterns seen in tumors, the study provides a mechanistic link between early-life microbiome exposure and carcinogenesis. These insights could guide new prevention strategies aimed at microbial pathways rather than host cells.

For decades, scientists have suspected that a mysterious toxin produced by common gut bacteria might be quietly shaping the earliest steps of colorectal carcinogenesis. Now a pair of coordinated studies from Harvard and the University of Minnesota provides the clearest picture yet of how colibactin, an elusive genotoxin made by certain E. coli strains, damages DNA, creates highly toxic lesions, and imprints a mutational scar that matches signatures found in human colorectal tumors, particularly in younger patients.

The work, published in Science, represents a technical and conceptual breakthrough in understanding how a microbial metabolite may act as a direct carcinogenic driver. It also opens the door to new prevention strategies aimed at microbes rather than human cells.

[link]healthandpharma.net/ctdna-blood-test-guides-chemotherapy-colon-cancer-treatment[/link]

“This molecule has been really challenging to study because it’s very chemically unstable,” said Emily Balskus, the Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of Chemistry at Harvard.

By leveraging in situ toxin production inside engineered bacteria, applying advanced mass spectrometry, and scaling nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, researchers managed to do what had long seemed impossible: capture colibactin in the act, trace its DNA targets, and determine the architecture of the interstrand cross-links it forms.

A Cross-Link That Locks DNA in Place

The double helix is ordinarily unwound and rewound thousands of times per day as cells replicate, repair, and transcribe their genome. Many mutagens damage one strand of DNA, but colibactin takes a more aggressive approach. It chemically fastens the two strands together, creating what is known as an interstrand cross-link.

“An inter-strand cross-link means that your DNA-damaging agent reacts with both strands of DNA,” Balskus said. “It links the two strands of DNA together, creating a particularly toxic form of DNA damage to the cell.”

Such lesions block replication forks, break chromosomes, and derail repair pathways. Over time, the resulting mutations can accumulate in patterns that are recognizable across genomes. That consistency is what first drew researchers to colibactin as a candidate driver of colorectal cancer.

Zeroing In on Colibactin’s Sequence Preferences

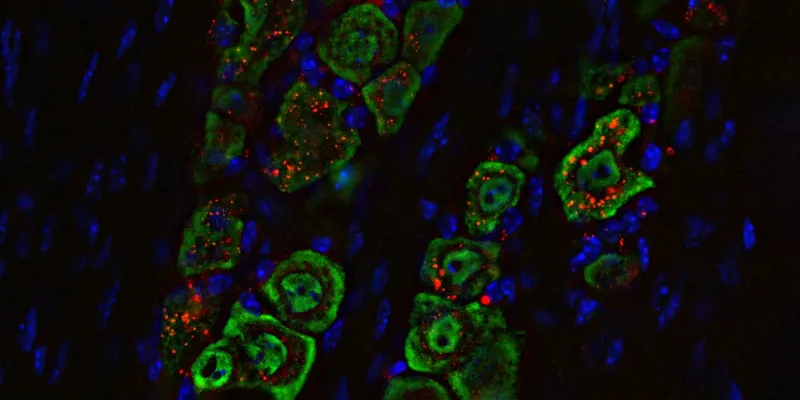

One central question stood in the way of progress: Does colibactin attack DNA at random, or does it favor specific sequences? By generating colibactin directly within living bacteria and exposing synthetic DNA fragments to the toxin, the team used classical gel-based mapping and high-resolution mass spectrometry to chart the locations of cross-links. The specificity proved striking. Colibactin consistently targeted a narrow AT-rich motif, identified as 5′-WAWWTW-3′, where adenine residues on opposing strands became alkylated to form bis-N3-adenine cross-links.

This selectivity mirrors the mutational signatures observed in human colorectal cancers, particularly in tumors arising in younger adults. The epidemiological connection became even more intriguing when researchers noted that colibactin-producing E. coli are most abundant in the infant gut microbiome, coinciding with a developmental window increasingly implicated in early-onset colorectal cancer risk. These insights prompted the next challenge: understanding why colibactin prefers AT-rich DNA.

Solving the Structure of an Unstable Lesion

To tackle this question, D’Souza’s team turned to NMR spectroscopy, an approach that typically requires substantial quantities of stable material, something colibactin has never offered. The resulting structural model finally provided the missing mechanistic explanation. AT-rich regions form a tighter, more negatively charged minor groove. Colibactin fits this space with unusual precision.

At the core of this fit is a positively charged α-ketoiminium group that anchors the toxin within the minor groove, reinforcing electrostatic and hydrogen-bond interactions. This functional group, previously hypothesized but never directly observed in situ, appears to dictate both the toxin’s reactivity and its sequence preferences.

Clinical Implications

The combined mass spectrometry and structural biology findings clarify the long-debated architecture of colibactin’s unstable central region and confirm that its pair of cyclopropane warheads can simultaneously alkylate opposing DNA strands. This represents a distinctive DNA-alkylation strategy among natural products and explains why cross-links form at predictable genomic locations.

These mechanistic insights deepen concern about the role of colibactin-producing microbes in colorectal carcinogenesis. They also highlight a promising opportunity. If a microbial metabolite is responsible for initiating or accelerating cancer-related mutations, then targeting the bacteria, their biosynthetic gene clusters, or the toxin itself could form the basis of new preventive interventions. The researchers emphasize that the work exemplifies the strength of interdisciplinary collaboration.

Colibactin is unlikely to be the only microbial metabolite influencing carcinogenesis, but it is now one of the best characterized. With a structural model, a defined sequence preference, and a direct molecular link to mutational patterns in colorectal cancer, the field has a new template for exploring bacteria driven genotoxicity.

Comments

No Comments Yet!